|

|

|

|

Travelog:

USA Nomads in America

Peru Void Touching

Bolivia

Walk the Rainbow Sweet Sucre Shamanic Verses Ever Upward Gettin' Home Rurrenabaque Chile Wheels of Jesus Valparaiso Argentina Waterfall Wonderland Buenos Aires Magic Boots The Fitz! The Fitz!! Dances w/ Bicycles 1 Dances w/ Bicycles 2 Brazil Inside the Toy Chest Moments from Rio The Island of Honey |

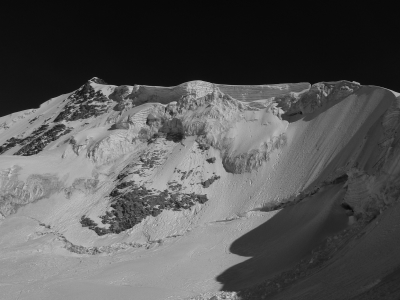

Ever Upward: Climbing 20,000 feet

Aug 1st, 2006

It was 7:00am and maybe 15F. 6000m (19,600ft) above sea level, I was climbing a 200m foot wall of ice and snow, crampons and ice axe fixing me on a precarious perch. I'd been trudging upward since 2am on zero sleep. As the sun pierced the cloudcover below in a red ball, I had no idea how to summon the energy for the last 100m to the snowy summit. Welcome to Bolivia, where for less than $50 a day, you can participate in any number of sports that can kill you. My expedition of choice: mountaineering on a peak just an hour outside La Paz. Huayna Potosi, with a snowy twin peak, is rumored to be the decapitated, relocated head of a young mountain whose pride swelled too large. It's a much calmer mountain these days. For the past two days, our international group of 7 (2 Israeli, 2 French, Spanish, Irish, me) had been acclimatizing in the base camp and high camps. We'd donned plastic boots (think low-top skiing), crampons, wielded the trusty piolet (ice axe) and tromped about on an old glacier that cast a shadow like the tsunami waves of old Japan. Our guides asked if we'd like to try something "a little tough" to practice -- that meant climbing up a fully vertical 30 foot wall of blue ice. It was a warm-up for the ascent that would begin in the middle of the night, 30 hours later. The agency I'd hired is run by a doctor who told me he gave up doctoring because he didn't want to make a living on people's pain. They own the refugio (refuge) at base camp and have well-trained guides that help people put themselves in pain in the middle of the night. Mountaineering is weird that way. Like a religion, it's complete with pilgrimages, myths of legendary climbers, and superstitions. Oddly enough, at the base camp refugio, I met a legend and his pair of disciples. Alan Burgess and his twin Adrian have climbed all the biggies: Everest, K2, and the gang. Jon Krakauer, author of "Into Thin Air", wrote about the duo in "Eiger Dreams." Sue and Jack are from San Diego on their 4-week reprieve from corporate life, guided by and supremely confident in Alan. They're acclimatizing on hikes above 5000m (16,400ft) to tackle some really big mountains: 6549m Sajama and 6402m Illimani. Both mountains are both much more "technical" than Huayna Potosi, meaning that they are better at killing people. "Cerebral edema, is the really bad one", Alan explained, "the blood-brain barrier in your skull breaks down and feels like a metal band cinched around your head." A nasty variant of altitude sickness, it can strike and kill within hours. Most of our group is sitting in rapt attention around Alan and the refugio fireplace, silently calculating our potential risks. Altitude sickness, or soroche, is the original sin of climbing, smiting those too proud to wait, grasping too high too fast. We have ascended from the relatively high La Paz (3600m), but the two Israelis had been in the jungle before that, essentially sea level. There was only nervousness and waiting to see if we were struck down. As we prepped in the high camp at 5200m, melting huge hunks of glacier for water and a 5pm dinner of pasta and hotdogs, I felt confident in my acclimatization. Nearly a month in Bolivia above 3000m -- surely enough to avoid smiting. But, between one of the Israelis and the wall, I couldn't sleep. Despite all my other good works, this single fact alone almost doomed me. We had stared up at the trail through the snow the day before. When the alarm finally keyed at 12:30, the group was anxious and ready. I'd heard the wind howling outside and wondered what we'd gotten ourselves into. Crawling into three pairs of socks, three pants, and four jackets, we started into darkness. I was paired with a guide, and Niamh ("Neev") an Irish gal with a 5900m Ecuadorian mountain already under her belt. The trail started almost immediately up a 45-degree incline. I found a rhythm of 3 steps -- right, left, piolet -- and looked ahead at climbers further up the mountain. Their headlamps glowed on the dark slope, like shooting stars recanting their decision. They were already far above us. It was not going to be a walk in the park. Mountaineering is a long walk in the dark with bad shoes. As Alan had explained, one must be as efficient as possible. One should also not lack of philosophic/recovery pauses. Our guide, Choco, apparently, wasn't of this school of thought. Despite repeated pleas, this man, strapped to us by rope and duty, constantly called out "vamos, vamos" (let's go). My fatigue reached a pinnacle about the time my patience hit zero. After marching ever upward, climbing an ice wall or two, we came to the last obstacle at 6:15, the 200m wall separating us from the summit. Dawn was breaking. We began to crawl up the wall, pausing after each 5 steps for breath. Choco belted out his refrain, "vamos", and then simply began to climb up without us. He let out over 100m of rope and scrambled upward. We cursed at him and decided that summiting like snails was just fine. Niamh and I, now on a slack rope, looked down to see the French couple call it quits as they reached the wall. One of the Israelis suffered beneath us, but with a more patient guide. With perfect clarity, and a fresh sun on my back, there was no rush. All I remember hearing was the crunch of my shoes and the ice axe, and my breath. The morning light felt good as the snow glinted in micromelt. Summitting was the only thing worth doing. We summitted the mountain at 7:45am on a beautiful, but fragile cornice. 6,088m -- 19,974 feet. Over the edge, a 300m sheer drop, and all around us, mountains set as islands in the clouds. Blue sky intense enough to paint with. But the ecstasy of mountaineering is temporary. After just 15 minutes of M&Ms and foolish photos, we began descent. I'm not sure when I'll return to God's perch up there. Mountaineers, despite warm laughs, are born in the cold, above the land where man belongs. I'm going to steal a Sherpa saying from Alan Burgess' book: "Maybe true, maybe not true; Better you believe." |

Snaps:

(All Bolivia)

|

.gif)